- When it comes to parents, their advice often boils down to simplistic statements like "Don't play with boys, or you'll get pregnant." I vividly recall the confusion I experienced when I got my first period.

I find myself in my early 20s, realizing that I have never had a candid conversation about sexual and reproductive health with my parents.

Like many African children, specifically in Kenya, my education system failed to provide comprehensive information on these critical topics.

Through the anecdotes of my friends, it becomes clear that our parents only scratched the surface when it came to addressing issues surrounding sex and reproductive health.

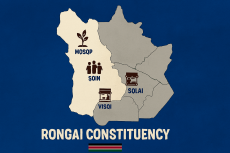

Growing up in Baringo County, the subject of sex and reproductive health was shunned by parents, the community, and even our schools, deeming it a taboo topic.

The limited exposure I had to reproductive health was in class six and form four, where we were given a brief overview of genital anatomy, sexually transmitted diseases, and genetics.

Read More

However, it was evident that our teachers were reluctant to delve deeper into these matters.

When it comes to parents, their advice often boils down to simplistic statements like "Don't play with boys, or you'll get pregnant." I vividly recall the confusion I experienced when I got my first period.

I genuinely thought something was wrong with me and immediately sought help from our maid. I explained to her that I was sick "down there" and that I was bleeding.

She chuckled and handed me something that resembled a diaper, which she helped me place in my underwear. It was only later that I learned it was called a pad.

Before that moment, menstruation was a vague concept to me, something briefly mentioned in school but never thoroughly explained, leaving us to cram the information for exams.

Young boys face their own set of challenges regarding sexual and reproductive health. Based on the experiences of my brothers and their friends, I discovered that they learned about these topics through their peers, often leading to detrimental consequences.

Influenced by their friends, some of them developed a habit of watching pornography, unaware of its distorted representation of healthy relationships and sexual experiences.

It is evident, both from personal experiences and the stories of others, that the lack of comprehensive sexual and reproductive health education is a significant challenge.

The saying goes, "My people perish for lack of knowledge." Kenya faced a disturbing surge in teenage pregnancies during the COVID-19 period, a situation that could have been prevented through proper education.

If students were taught about contraceptives and sexual issues in a clear and unfiltered manner in schools, perhaps they would have chosen abstinence for the right reasons.

While I understand that contraceptive use presents a contentious issue with religious and moral concerns in Kenya, disregarding the reality that teenagers are engaging in sexual activities, as indicated by data from the Demographic and Health Surveys, is detrimental.

Approximately 2 out of 10 girls between the ages of 15 and 19 are reported to be pregnant or have already given birth.

It saddens me that Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) persists in Kenya. My mother once confided in me that she had undergone the cut. This revelation baffled me, as it was only a generation away from mine.

It dawned on me that if we were still living in the interior parts of Baringo, there was a possibility that I would have been subjected to this practice.

Despite the National Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Policy being against FGM, some communities staunchly continue this archaic tradition in secret.

Moreover, remote areas in Kenya lack sufficient, safe centres where young girls can seek refuge and assistance when they find themselves in need.

In Kenya, even the act of purchasing a condom as a young person can be emotionally wrecking. The judgmental eyes of shopkeepers and their potential reprimands create an environment of shame and embarrassment.

Healthcare workers, who should ideally provide a non-judgmental space for individuals to express their concerns, often act as barriers to reproductive healthcare services.

I recall a distressing experience when I went for an HIV testing session, and the doctor refused to test me, insisting that unless I had recently engaged in sexual activity (specifically within the past three months), there was no point in testing.

I persisted in asking why I couldn't be tested, especially when the testing was free. After much coercion, they reluctantly conducted the test, but the pre-counselling session was filled with attempts to force me to admit that I had engaged in sexual activity.

The doctor even inquired about my parents' identity. She warned me against entering into early relationships when the results were negative. I left that clinic feeling judged and misunderstood.

If seeking a simple HIV test can be such a daunting experience, how much more challenging would it be to seek advice on appropriate contraceptive methods?

Young girls often resort to misusing emergency contraceptive pills because their friends offer advice without considering the long-term effects on personal health. When healthcare providers are judgmental, young adults are driven to seek help in all the wrong places.

Kihika's Reproductive Health Care Bill became a battleground for advocates who recognized the urgent need for comprehensive sexual and reproductive health education.

This bill aimed to address the gaps in current policies and provide a framework for providing quality reproductive health services.

It emphasized the importance of age-appropriate education, access to contraceptives, and the establishment of youth-friendly health centres. While the bill faced opposition from conservative groups, it sparked a much-needed conversation about the rights and well-being of young individuals in Kenya.

To bridge the gap in sexual and reproductive health education, public awareness campaigns and media platforms could play a crucial role.

Television shows, radio programs, and social media campaigns could disseminate accurate information, debunk myths, and create a safe discussion space. By normalizing conversations about sex and reproductive health, we can gradually break down the barriers and stigma surrounding these topics.

-1770826318-md.jpg)

-1770803686-md.png)

-1770826318-sm.jpg)

-1770803686-sm.png)